Throughout their career, American photographer Lola Flash has often focused on social, political, LGBTQ, and feminist issues. Flash is of African American and Native American heritage. Growing up in Montclair, New Jersey, they developed an interest in photography as a young girl, eventually photographing students for the school yearbook. In 1981 Flash earned her B.A. at Maryland Institute College of Art and later attended the London College of Printing, where she received her M.A.

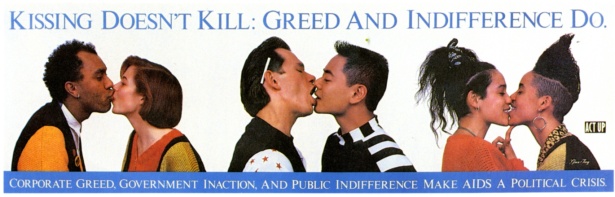

Flash’s originally intended to focus on science photography but switched focus throughout her studies. Her style of photography is primarily portraiture, focusing on queer people of color and others who are often marginalized or ‘invisible’ within both the art community and the larger community as a whole. In 1987, Flash was heavily involved with ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), a New York grassroots organization with the goal of improving the lives of those living with HIV/AIDS through direct action, research, and advocacy. Through this involvement, she appeared in Gran Fury’s Kissing Doesn’t Kill public service campaign poster. This poster appeared on billboards, busses, and subway platforms in multiple U.S. cities to destigmatize the gay community in the wake of the AIDS epidemic.

During this time, the Flash produced many of the photographs that would become her Cross Color Series. In this series, Flash used slide film and developed her photos on negative paper, which resulted in a striking inverted color scheme. Flash used this effect as a means to challenge the viewer’s perceptions and challenge stereotypes that are often held about the LGBTQ community. “The inverted stylized portraits make the subjects appear larger than life and otherworldly because, in a sense, they are. The individuals within the images live life freely and do not allow the constraints of societal pressures to make them conform (Lee, 4).” Flash’s art and activism are profoundly intertwined, exposing a commitment to recording and preserving the mark left by the LGBTQ community and communities of color.

And I started thinking about, well, actually what I’m doing is I’m reversing the colors…so I started thinking black is white and my pictures and white is black. I’m sure I remember reading that black was bad. That black was, was dirty. It was wrong. Right? But white it was beautiful. Perfect. Right. Angelic. Growing up as a little black girl in New Jersey. You know, I never talked to anyone about that, but I think it’s kind of laid heavy on my shoulders. And so I was thinking, wow, what I’m doing is I’m actually changing the people, right? So no longer are black people bad. They’re good.

Lola Flash on her Cross Color Work

Flash’s most recent work has focused on genderfluidity and how skin color impacts black identity. In her current series, Syzygy, the vision, Flash becomes the subject, exploring the themes of racism, sexism, and homophobia. This series of self-portraits is Afrofuturist, a cultural aesthetic that explores the African diaspora (the collective global communities of African descent) as it intersects with science, philosophy, and technology.

Flash continues living in New York City, where she teaches visual arts and English at a Brooklyn high school. Her work is held in a permanent collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Further Reading

http://www.lolaflash.com/aidsflashbackcrosscolour

https://www.wmnzine.com/lola-flash-artist-talk/

“Photographer Lola Flash is honored for creating images that challenge invisibility.” All Things Considered, 14 Dec. 2021, p. NA. Gale In Context: Environmental Studies, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A687551369/GRNR?u=s8405248&sid=bookmark-GRNR&xid=18aa920a. Accessed 10 Mar. 2023.

Moore, Lisa. Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol. 4, no. 2, 1993, pp. 324–27. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3704304. Accessed 10 Mar. 2023.

Check out the gallery for some of my photographs inspired by Lola Flash’s work.